Authors:

Edward J Sinkule*

Department of Natural Science and Engineering Technology, Point Park University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 15222, USA

Received: 11 August, 2015; Accepted: 28 August, 2015; Published: 31 August, 2015

Edward J Sinkule, Point Park University, Department of Natural Science and Engineering Technology, 201 Wood Street, Room 605 AH, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222, Tel: (412) 386-4054; Fax: (412) 386-6864; E-mail:

Sinkule EJ (2015) A Review of the Possible Effects of Physical Activity on Low-Back Pain. J Nov Physiother Phys Rehabil 2(2): 035-043. DOI: 10.17352/2455-5487.000023

© 2015 Sinkule EJ. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Low back pain; Physical activity; Rehabilitation; Therapeutic exercise

Objective: Low back pain (LBP) represents the most prevalent and costly repercussion from musculoskeletal injury in the work place. This review examines the earlier and current research reported on the significance of physical activity on musculoskeletal injuries and LBP, the benefits and limitations of therapeutic exercise, and the potential features of various exercise modalities that may contribute to the secondary and tertiary prevention of low-back pain.

Methods: A search was performed using MEDLINE to identify original studies published in English from January 1990 to December 2013. Physical activity in the form of aerobic, muscle strengthening, flexibility, and occupational (labor) activities among working adults (18 – 65 years of age) alone and with other non-surgical therapies were selected. A hand-searched collection from a personal literature library also was used.

Results: Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria, addressing aerobic exercise (n=4), muscle strengthening exercise (n=3), combination of aerobic, muscle strengthening, and flexibility exercises (n=5), and occupational labor/exercise (n=3). The investigations generally supported the benefits of programmed and structured exercise alone and with other therapies for the treatment of LBP.

Conclusions: Given the physical and financial burden to treat LBP, this issue remains a great public health importance. With the burden on society from LBP and the prevalence of the disorder among populations, research from physical activity on LBP has produced varied results without a specific type of exercise that results in resolved LBP better than most. Most agree that some activity is better than none, but no one activity is better than the others when the multifactorial etiology of LBP remains inconsistent. Isolating the vertebrae that causes the LBP would be beneficial for participant selection with future research. Different forms of pathological evidence or combinations of pathological measurements may help to establish proof of beneficial exercise or a combination of exercise therapies.

Introduction

Occupational musculoskeletal injuries are a major cause of disability and worker absenteeism [11. Karvonen MJ, Viitasalo JT, Komi PV, Nummi J, Järvinen T (1980) Back and leg complaints in relation to muscle strength in young men. Scand J Rehabil Med 12: 53-59.]. Most musculoskeletal injuries in the work place are sprains & strains, dislocations, and fractures [22. Kelsey JL (1982) Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Disorders. Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics. 3: New York: Oxford University Press.]; in addition to inflamed joints [33. Sinkule EJ, Nelson RM, Nestor DE (1986) Musculoskeletal injuries in an aging workforce. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Engineering in Medicine and Biology. Baltimore, Maryland: Alliance for Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 364.]. The most frequent cause of musculoskeletal injuries involve over exertions [33. Sinkule EJ, Nelson RM, Nestor DE (1986) Musculoskeletal injuries in an aging workforce. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Engineering in Medicine and Biology. Baltimore, Maryland: Alliance for Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 364.,44. Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.], and bodily reactions [33. Sinkule EJ, Nelson RM, Nestor DE (1986) Musculoskeletal injuries in an aging workforce. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Engineering in Medicine and Biology. Baltimore, Maryland: Alliance for Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 364.]. Over exertions more commonly involve lifting or pushing/pulling of objects [44. Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.]. Among sprains/strains, the back is the most injured body part [22. Kelsey JL (1982) Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Disorders. Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics. 3: New York: Oxford University Press.]; in addition to all bodily joints, which included the back [33. Sinkule EJ, Nelson RM, Nestor DE (1986) Musculoskeletal injuries in an aging workforce. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Engineering in Medicine and Biology. Baltimore, Maryland: Alliance for Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 364.,55. Cunningham LS, Kelsey JL (1984) Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am J Public Health 74: 574-579.].

The health risks from leisure-time physical activity are shared by occupational activity. The etiology of occupational musculoskeletal injuries has been implied to be similar to the principles of muscle strength training [77. Guthrie DI (1963) A new approach to handling in industry. A rational approach to the prevention of low-back pain. S Afr Med J 37: 651-655.]. The uncontrollable factors that contribute to the possible etiology of musculoskeletal injuries in the work place include the following: repetitive motions at abnormal speeds [88. Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.]; static muscle work [88. Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.]; abnormal work positions [88. Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.]; repetitive lifting [88. Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.]; position transfers [88. Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.]; required apparel [88. Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.]; monetary incentives [44. Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.]; and social or family pressure [44. Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.]. When work is performed according to production expectations, the increase in metabolism potentially could exacerbate complications from underlying cardiovascular disease. Results from studies which examined the heart rate response of workers performing tasks, ad libitum, responded within an acceptable limit for eight hours of work, however, some of the subjects had heart rates higher than expected for the same tasks [44. Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.].

Physical activity has been used as a form of primary prevention for musculoskeletal injuries from exercise. Therefore, it follows that physical activity may be a potential factor in treatment or prevention of low-back pain and injury in the work place as well. With the increased awareness in health promotion and injury/illness prevention, the increased importance of physical activity has been recognized in the public health literature as a crucial element for optimal health. The health benefits of physical activity can be categorized as physical (e.g., cardiovascular, orthopedic, flexibility, and musculoskeletal), psychological, and perhaps, economical.

The primary, longitudinal purpose of physical activity has been to improve physical health. For the 2020 Healthy People objectives, the target uses an increase in adults engaged in regular moderate (unknown metabolic equivalent) physical activity above 43.7% (the base year of 2008) and an increase in adolescents engaged in federal-recommended regular physical activity above 18.4% (the base year of 2009) [1414. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2014) Physical Activity, Related Objectives (Adults). Department of Health and Human Services. ,1515. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2014) Physical Activity, Related Objectives (Adolescents). Department of Health and Human Services. ].

Theoretically, those with a higher physical work capacity (PWC) can perform submaximal exercise, including activities of daily living, with a reduced effort thereby reducing fatigue [1010. Nachemson A (1969) Physiotherapy for low back pain patients. A critical look. Scand J Rehabil Med 1: 85-90.]. The gains from physical activity also have included increases in muscular strength for different ages and gender [66. Kosiak M, Aurelius JR, Hartfiel WF (1968) The low back problem - An evaluation. Journal of Occupational Medicine 10: 588-593.]. How the level of activity can effect occupational performance has received attention of health experts in the United States. This attention is based on the theoretical principles of exercise physiology and psychology: if functional capacity can be improved, then the capacity to work at one’s chosen occupation also can be improved.

Whether muscle strengthening exercise can be effective in prevention and/or treatment of low back pain from injury is unclear. Currently, it is known that those who suffer from LBP have reduced strength in the trunk extensor muscles; low muscle endurance contributes to LBP; and minimal trunk strength is necessary to return to normal function [1818. Jackson CP, Brown MD (1983) Is there a role for exercise in the treatment of patients with low back pain? Clin Orthop Relat Res 179: 39-45.]. It is not certain whether exercise contributes to function or to reduction of pain or both [1818. Jackson CP, Brown MD (1983) Is there a role for exercise in the treatment of patients with low back pain? Clin Orthop Relat Res 179: 39-45.]. Conditioning exercises have been used to decrease the degree of incapacity accompanying low back dysfunction [1818. Jackson CP, Brown MD (1983) Is there a role for exercise in the treatment of patients with low back pain? Clin Orthop Relat Res 179: 39-45.]. In a study of 20 occupations within a tire & rubber plant that examined the effects of pre-employment strength tests on the employee’s physical capacity to qualify for jobs, investigators reported a 3-fold greater incidence of medical visits by control groups over the experimental group [1919. Keyserling WM, Herrin GD, Chaffin DB (1980) Isometric strength testing as a means of controlling medical incidents on strenuous jobs. J Occup Med 22: 332-336.]. In addition, the experimental group did not incur any visits to treat musculoskeletal injuries of sprains or strains. The investigators did not examine the effect of job transfers as a way of bypassing the screening.

The use of physical activity to improve joint flexibility is vague. Buskirk reviewed reports that supported the use of chronic physical activity toward the improvement of flexibility within elderly males and females [1919. Keyserling WM, Herrin GD, Chaffin DB (1980) Isometric strength testing as a means of controlling medical incidents on strenuous jobs. J Occup Med 22: 332-336.]. A historical research report by Panush [2121. Panush RS, Schmidt C, Caldwell JR, Edwards NL, Longley S, et al. (1986) Is running associated with degenerative joint disease? JAMA 255: 1152-1154.] and a prospective study by Rhodes [2222. Rhodes EC, Dunwoody D (1980) Physiological and attitudinal changes in those involved in an employee fitness program. Can J Public Health. 71: 331-336.] were inconclusive when tests were applied to exercise and control groups in an effort to detect a significant difference in flexibility between groups.

The objective of this investigation will concentrate on the most prevalent and costly repercussion from musculoskeletal injury in the work place, i.e. LBP from injuries. The following narrative review will examine the earlier and current research reported on the significance of physical activity on musculoskeletal injuries and LBP, the benefits and limitations of physical activity, and the potential features of physical activity that may contribute to the secondary and tertiary prevention of low-back pain.

Methods

For the purpose of providing results from the past 35 years of exercise research on LBP, two sources were used to identify articles published for this review. The first source was a bibliographic database by the United States Library of Medicine, MEDLINE. The MEDLINE was used to search for literature from 1990 to 2013 in English on the relationship of exercise and low-back pain. Abstracts were used to preview relevant, original articles with a search of key words: “exercise”, “musculoskeletal training”, “physical activity”, “physical work capacity”, “flexibility”, “occupational”, “low-back pain”, and “low-back injuries”. Studies were selected that provided a representative sample of separate exercise modalities for comparison. The randomized controlled trial was a preferred design. Many studies that reported similar results were not included in this review. The second source was a 35-year personal collection of exercise literature on low-back pain/injuries and was hand-searched. Inclusion of the older studies provided a foundation of results that has not been published previously with contemporary study results.

The availability of relevant manuscripts from personal archives provided information that was collected before the inception of the world-wide web. Many of the available sources were used as primary sources from related literature (also known as cross-references). Experts agree little has changed over time in the study of physical activity for the primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of low-pain pain and disability [2323. (2009) Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. To the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Part A: executive summary. Nutr Rev 67: 114-120.].

Results

Aerobic exercise

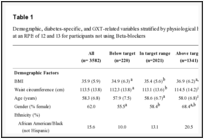

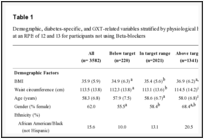

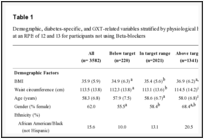

The effects from aerobic activities on LBP are presented in Table 1. As a form of physical activity, chronic aerobic exercise has been used for the strength improvement of the ligament-bone integrity at the joint. Tipton examined the morphologic ligamentous connection in rats and dogs treated with physical activity and immobilization [2424. Tipton CM, Matthes RD, Maynard JA, Carey RA (1975) The influence of physical activity on ligaments and tendons. Med Sci Sports 7: 165-175.]. This research further cited a strong correlation between junction strength with body weight and a weak correlation with ligament mass; thereby suggesting different mechanisms representing the effects of physical activity on junction strength and on ligament mass. Similar results with repaired ligaments have been reported. Human studies have cited a reduction in joint stiffness, maintenance of muscle tone and proper posture with aerobic exercise [2525. Harkcom TM, Lampman RM, Banwell BF, Castor CW (1985) Therapeutic value of graded aerobic exercise training in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 28: 32-39.]. Effects of physical activity on improved levels of subjective low back pain from injury have been reported [1111. Dehlin O, Berg S, Hedenrud B, Andersson G, Grimby G (1978) Muscle training, psychological perception of work and low-back symptoms in nursing aides: The effect of trunk and quadriceps muscle training on the psychological perception of work and on the subjective assessment of low-back insufficiency. A study in a geriatric hospital. Scand J Rehabil Med 10: 201-209.]. From this activity, strong tendons, ligaments, joint cartilage, connective tissue sheaths, tendon-to-bone and ligament-to-bone junction strength, and bone mineral content augment injury prevention. Physical activity, in one form or another, has been advised for prophylaxis from sport injuries and occupational trauma [2626. Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC (1986) Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med 314: 605-613. ].

Physical activity can reverse joint stiffness across various age groups. Chapman et al. (1972) examined the effects of physical activity on joint stiffness in two groups of males, 15-19 years and 63-88 years of age [2727. Chapman EA, deVries HA, Swezey R (1972) Joint stiffness: Effects of exercise on young and old men. J Gerontol 27: 218-221.]. The results demonstrated that joint stiffness, in both young and old individuals, is a reversible phenomenon. In a study of active (treatment) and inactive (control) employees, Chenoweth used an aerobic exercise program to examine effects on volunteer participants [2828. Chenoweth D (1983) Fitness program evaluation: Results with muscle. Occup Health Saf 52: 14-17, 40-42.]. The exercise program met for 45-60 minutes twice each week for 12 weeks. The description of exercise intensity was light calisthenics and stretching to strenuous jumping, hopping, and modified running activities. Of the significant results for the 12-week program, increased back flexibility and decreased absenteeism was reported for the treatment group, in addition to modest decreases in resting heart rate (2.5 beats per minute), systolic blood pressure (2.3 mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (2.6 mmHg), body weight (1.6 pounds), and body composition (2.1% body fat).

Harkcom et al. (1985) reported favorable results after examining levels of joint stiffness in rheumatoid arthritis patients in exercise programs of varying levels [2525. Harkcom TM, Lampman RM, Banwell BF, Castor CW (1985) Therapeutic value of graded aerobic exercise training in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 28: 32-39.]. Participant volunteers consisted of a cohort of selected 20 women with rheumatoid arthritis of various severity and treatments but consistent with stable treatment regimens stable drug therapies and no steroid injections received before or during the study. The intervention included three groups of increasing durations each session (Group-A, 2.5 to 13 minutes (n=4); Group-B, 7.5 to 24 minutes (n=3); and Group-C, 15 to 35 minutes (n=4)), during the 12-week program of bicycle ergometry compared to sedentary controls (n=6) selected among the initial volunteers. Pre- and post-treatment evaluations included self-perception of exertion for activities of daily living and joint pain, grip strength, a walking test, muscle strength measured at the knee, and a graded exercise test of aerobic capacity using a bicycle ergometer. Significant improvements included aerobic capacity (for each treatment group, versus baseline), exercise test time (for each treatment group, versus baseline), joint pain (for each treatment group, versus baseline), and muscle strength (Group-B only, versus baseline). The exercising group also reported a decrease in the scores for pain and swelling, morning stiffness and improved sleep patterns.

Chan et al. [2929. Chan CW, Mok NW, Yeung EW (2011). Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition to Conventional Physiotherapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92: 1681-1685.], studied the effects of aerobic exercise in addition to conventional physiotherapy for patients with LBP. Their cohort consisted of 46 men and women selected for treatment or control by randomization. Treatment patients engaged in aerobic exercise (treadmill walking, cycling, or stepping) for eight weeks under the supervision of a physical therapist at an intensity of 40-60% of heart rate reserve for 20 minutes, three meetings each week of which one was unsupervised home-based exercise. Outcome variables included pain, functional disability, and physical fitness using aerobic capacity, back extensor muscle endurance, low-back and hamstring flexibility, and body composition (% body fat). After eight weeks, the treatment group improved for all outcome variables where the control group only improved for body composition and back flexibility. At 12 weeks, both groups improved both pain and disability scores when compared to baseline.

Sculco et al. [3030. Sculco AD, Paup DC, Fernhall B, Sculco MJ (2001) Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J 1: 95-101. ], examined the effects of aerobic exercise alone for the treatment of LBP of various pathologies. Participants included 35 patients from a neurosurgical practice at a tertiary care teaching hospital and were not receiving treatment for cardiovascular disease, current acute severe LBP, or low-back surgery within six months. The intervention included a 10-week home-based exercise program of walking or cycling, four days each week at 60% of their age-predicted maximum heart rate, beginning at 20 minutes and progressively increasing exercise duration to 45 minutes/period. Outcomes (pain and mood state inventories) were measured at 10-weeks and 30-months. At 10-weeks, the active group reported, fewer injuries, less depression, anger, and total mood disturbance compared to controls. At 30-months, the physically active group filled fewer pain prescriptions, needed fewer physical therapy referrals, and improved their work status compared to controls.

Indirect benefits from fitness programs include fewer medical claims filed and reduced costs from the medical claims [3131. Davis MF, Rosenberg K, Iverson DC, Vernon TM, Bauer J (1984) Worksite health promotion in Colorado. Public Health Rep 99: 538-543.-3434. Gibbs JO, Mulvaney D, Henes C, Reed RW (1985) Work-site health promotion: Five-year trend in employee health care costs. J Occup Med 27: 826-830.]. One report which reviewed an aerobic fitness program over a four year period for men (age range = 35-55 years) cited no difference in the number of claims filed between compliers and non-compliers or those who dropped out of the program [3535. Chen MS, Jones RM (1982) Establishing priorities in the wellness program. Occup Health Saf 51: 6-7, 36.]. However, the average cost per claim for the non-exercisers was two times the cost of the claims submitted by those who participated in the exercise program [3636. Martin J (1978) Corporate health: A result of employee fitness. The Physician and Sportsmedicine; 6: 135-137.]. In an evaluation of a corporate fitness program comparing short term participation (18-30 months) and long term participation (>30 months) to those who did not participate, a lower charge rate in hospital costs was reported by both exercise groups compared to the non-exercising controls; age was associated with increased medical costs and utilization; gender was related to medical costs, i.e. women incurred higher costs and more utilization than men; and salaried workers incurred lower medical costs and utilization rates compared to wage earners [3636. Martin J (1978) Corporate health: A result of employee fitness. The Physician and Sportsmedicine; 6: 135-137.]. The reports by Chan and Sculco also present the indirect benefits from aerobic activity, such as improved mood states, reduced pain, less pain medication and return to work [2929. Chan CW, Mok NW, Yeung EW (2011). Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition to Conventional Physiotherapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92: 1681-1685.,3030. Sculco AD, Paup DC, Fernhall B, Sculco MJ (2001) Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J 1: 95-101. ].

Muscular strength and endurance

The relationships of muscular strength and endurance on LBP are presented in Table 2. Hemborg et al. (1983) investigated the involvement of the abdominal muscles and back muscles during lifting in healthy young men [3737. Hemborg B, Moritz U, Hamberg J, Löwing H, Akesson I (1983) Intraabdominal pressure and trunk muscle activity during lifting -- effect of abdominal muscle training in healthy subjects. Scand J Rehabil Med 15: 183-196.]. The subjects were tested using a standardized testing protocol before and after a five week exercise program specifically aimed at improving the strength of the abdominal and back muscles by isometric exercise. The results included improving the strength of the abdominal and back muscles, however, the investigators discovered that intra-abdominal pressure had not changed during the lifting tasks. In addition, the activity of the back muscles during lifting had not changed as a result of the training. In an investigation by Chapman and Troup (1969), a 14 day exercise program for developing the erector spinae muscles in 13 young adult males proved a significant linear relationship between electrical activity by the muscles and the force produced by lumbar musculature [3838. Chapman AE, Troup JDG (1969) The effect of increased maximal strength on the integrated electrical activity of lumbar erectores spinae. Electromyography 9: 263-280.].

-

Table 2:

Summary of studies investigating the relationship between muscle strengthening activity with LBP and health.

The strength of the trunk flexors is inversely related to backache and back pain associated with bending forward and lifting [11. Karvonen MJ, Viitasalo JT, Komi PV, Nummi J, Järvinen T (1980) Back and leg complaints in relation to muscle strength in young men. Scand J Rehabil Med 12: 53-59.]. Weak leg flexors have been related directly to lost workdays from back pain [11. Karvonen MJ, Viitasalo JT, Komi PV, Nummi J, Järvinen T (1980) Back and leg complaints in relation to muscle strength in young men. Scand J Rehabil Med 12: 53-59.]. Aerobic exercise in the form of walking and running has been related to improve back flexibility [2828. Chenoweth D (1983) Fitness program evaluation: Results with muscle. Occup Health Saf 52: 14-17, 40-42.].

Insufficient activity that strengthens abdominal muscles is associated with an increased risk of low back pain. The musculoskeletal integrity of intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic and trunk muscles influences the maintenance of posture during various lifting and carrying tasks [1010. Nachemson A (1969) Physiotherapy for low back pain patients. A critical look. Scand J Rehabil Med 1: 85-90.]. Increasing intra-abdominal and intra-thoracic pressure in order to relieve the load from the lumbar spine is the rationale for improving muscular strength of the abdominal and trunk muscles with isometric abdominal muscle exercises. Conversely, Nachemson reported a study of isometric testing of normal and low back injured from chronic over use; no significant differences were noticed in abdominal strength between the groups for males and females [4040. Nachemson A, Lindh M (1969) Measurement of abdominal and back muscle strength with and without low back pain. Scand J Rehabil Med 1: 60-63.].

Bone mineral content (BMC) of the axial skeleton improves from physical activity. As levels of physical work capacity increase, there appears to be an associated increase in the BMC of the lumbar spine. In a study examining activities of daily living in postmenopausal females and muscle strengthening exercise in world class power lifters, the positive correlation between activity and lumbar BMC was intact [3939. Granhed H, Jonson R, Hansson T (1987) The loads on the lumbar spine during extreme weight lifting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 12: 146-149.]. An additional point by the power lifter study suggested limitations in the linear relationship between the bone mineral of the lumbar spine and the compressive strength, i.e. when BMC exceeds a certain level, compressive strength does not increase concomitantly.

Combinations of aerobic, joint flexibility, and muscle strengthening activities

The effects from combinations of aerobic, flexibility, and muscle strengthening exercise on LBP are presented in Table 3. Probably the most cited report where physical activity was used to prevent occupational low back injuries was a prospective study to evaluate strength and fitness measurements and the subsequent incidence of back injuries in 1,652 firefighters (ages 20-55) from 1971-1974 [4141. Cady LD, Bischoff DP, O'Connell ER, Thomas PC, Allan JH (1979) Strength and fitness and subsequent back injuries in firefighters. J Occup Med 21: 269-272.,4242. Cady LD Jr, Thomas PC, Karwasky RJ (1985) Program for increasing health and physical fitness of firefighters. J Occup Med 27: 110-114.]. Prospective measurements included flexibility, muscle strength, and physical work capacity as measured on a bicycle ergometer. Subsequent incident cases of low back injuries were tabulated for different categories of fitness. Results included a higher percentage of injuries in the least fit group. The most costly injuries were in the fit group, however, this result was skewed by a low number of incident cases in the group (two), one of which cost $130,000.

-

Table 3:

Summary of studies investigating the relationship between combinations of aerobic activity, joint flexibility activity, and muscle strengthening with LBP and health.

Kohles et al. [4343. Kohles S, Barnes D, Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG (1990) Improved physical performance outcomes after functional restoration treatment in patients with chronic low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15: 1321-1324. ], examined two groups of patients with chronic LBP with a pretreatment program lasting 1-2 weeks (Group 1) and another that lasted 2-6 weeks, including aerobic exercise and muscle strength training (Group 2). Group 2 not only exhibited greater isokinetic trunk strength compared to Group 1, they also exhibited trunk strength similar to normal, unaffected controls. The differences also were seen for improved range of motion of the back and hip joints. The combined greater education, aerobic, muscle strength and flexibility activities proved to decrease inhibitory factors (e.g., pain or reinjury) and increased physical capacity.

Van der Velde and Mierau [4444. van der Velde G, Mierau D (2000) Effect of exercise on percentile rank aerobic capacity, pain, and self-rated disability in patients with chronic low-back pain: a retrospective chart review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81: 1457-1463.] determined the effects of aerobic, muscle strengthening, and flexibility exercise on measures of pain and disability in patients with LBP. The exercise program (aerobic exercise, muscle strengthening, and joint flexibility) lasted 10 months with data collected through chart reviews of patient changes. Patients with pain of the cervical and thoracic regions were included. In addition to improvements in aerobic capacity above the normal range for a similar cohort of healthy participants, pain levels were lowered significantly and disability scores were lower in the exercise group compared to pre-treatment measurements.

Vad et al. [4545. Vad VB, Bhat AL, Tarabichi Y (2007) The role of the Back Rx exercise program in diskogenic low back pain: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88: 577-82.], used LBP patients with a consistent pathology (disk degeneration) with leg pain which lasted 3+ months as the study cohort. The intervention included a specialized treatment program of muscle strengthening and endurance (physical therapy and Pilates), joint flexibility (yoga), and prophylactic body positioning that avoids intradiskal pressure with medical therapy and cryogenic bracing (Group I) compared to medical therapy and cryogenic bracing alone (Group II). The outcome variables include a disability inventory, a pain rating, patient satisfaction score, hip flexion, amount of medical therapy used, occupational absenteeism, and symptom recurrence. At a 12-month follow-up period, 70% of Group I exhibited a 50% reduction of pain and good patient satisfaction or better compared to Group II. In addition, Group I participants used less medical therapy each day, reported less absenteeism at work, and less symptom recurrence for the 12-month period.

A well-controlled study of concentrated and focused physical activities on LBP and oxygenation of back muscles and blood volume was conducted by Olivier et al. [4646. Olivier N, Thevenon A, Berthoin S, Prieur F (2013) An Exercise Therapy Program Can Increase Oxygenation and Blood Volume of the Erector Spinae Muscle During Exercise in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94: 536-42.]. Participants included 24 cases and controls, each included 12 men and 12 women. Potential participants with any other pathologic disorders were excluded from participation. The exercise intervention lasted for 5 hours of treatment each day for 5 days/week and 4 weeks. Activities were strengthening isotonics, aerobic conditioning, and global reconditioning. Improvements for the treatment group included greater oxygenation and blood volume of the erector spinae muscles during a progressive isoinertial lifting evaluation. Greater maximal loads lifted, total power, and total work were exhibited by the treatment group at the end of the 4-week treatment compared to baseline.

Occupational activity and LBP

A summary of the relationship between occupational activities and LBP is described in Table 4. Several investigators have examined the relationship of occupational activity patterns and the activity patterns associated with non-occupational activity. A considerably higher proportion of average activity occurred at work compared to after work activity or off day activity, and work activity represented as much as 69% of the total daily activity [4747. LaPorte RE, Montoye HJ, Caspersen CJ (1985) Assessment of physical activity in epidemiologic research: Problems and prospects. Public Health Rep 100: 131-146.]. A direct relationship existed between activity patterns at work and activity patterns after work [4747. LaPorte RE, Montoye HJ, Caspersen CJ (1985) Assessment of physical activity in epidemiologic research: Problems and prospects. Public Health Rep 100: 131-146.]. After work activity was not related to off day activity [4747. LaPorte RE, Montoye HJ, Caspersen CJ (1985) Assessment of physical activity in epidemiologic research: Problems and prospects. Public Health Rep 100: 131-146.]. Results from the 1985 National Health Interview Survey suggests that those who work in moderately active occupations made more attempts to be active during leisure time; however, those who worked light occupations had the greatest proportion of leisure physical activity that could be classified as regularly active with appropriate amounts of physical activity [4848. Caspersen CJ, Christenson GM, Pollard RA (1986) Status of the 1990 physical fitness and exercise objectives -- evidence from NHIS 1985. Public Health Rep 101: 587-592.]. Rose and Cohen attempted to determine how aging affects the patterns of occupational and leisure physical activity by examining the interviews from survivors of 500 white males who died in the Boston area [4949. Rose CL, Cohen ML (1977) Relative importance of physical activity and longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 301: 671-702.]. Occupational and leisure activity measures decreased as age increased. Leisure activity patterns were lower than occupational activity, the greatest differences occurred in the middle decades of life. Across the age strata, leisure activity has the tendency to decrease at an earlier age compared to occupational activity. The rationale for sustained occupational activity with increasing age was dependent on the demands of the job, where leisure activity was subject to changes with aging and life styles. The occupational activity patterns with aging were unrelated to the aging patterns of leisure activity.

-

Table 4:

Summary of studies investigating the relationship between occupational activity with LBP and health.

La Rivieve and Simonson examined the speed of handwriting as it varied with age and occupation [5050. LaRiviere, J.E. & E. Simonson (1965). The effect of age and occupation on speed of writing. Journal of Gerontology; 20: 415-416.]. The investigation showed a systematic decrease in handwriting speed with increasing age in those occupations where handwriting was not a major part of the job; therefore, there was no slowing in the responses associated with occupations which had repetitive demands. Sick leave, or absenteeism, was found to be unrelated to leisure activity. Magora reported that the amount of sick days reported by workers who were physically active after work were not statistically different from the amount of sick days reported by workers who were sedentary after work [5151. Magora A, Taustein I (1969) An investigation of the problem of sick-leave in the patient suffering from low back pain. IMS Ind Med Surg 38: 398-408.].

The effects from variations of the occupational demands have been shown to be associated with increased risk of low back injury. Conversely, studies exist which have shown no relationship between physically heavy work and low back injury and pain [1212. Andersson GBJ (1981) Epidemiologic aspects on low-back pain in industry. Spine 6: 53-60. ]. Suggestions of resistance to injuries, like resistance to infection, exist as natural or acquired [5252. Haddon, W. & S.P. Baker (1981). Injury control. In, Prevention and Community Medicine, Second Edition. Edited by Duncan W. Clark and Brian McMahon. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Co., 109-140.]. The response of tissues to repeated exposure of stress or strain has not been assessed adequately [5353. Andersson GBJ (1985) Permissible loads: Biomechanical considerations. Ergonomics 28: 323-326.]. When sick leave was examined, no statistically significant relationship existed between absenteeism and the employee’s perception of the occupational requirements or absenteeism and the employee’s opinion that the low back injury was caused by the occupation [5151. Magora A, Taustein I (1969) An investigation of the problem of sick-leave in the patient suffering from low back pain. IMS Ind Med Surg 38: 398-408.].

When Wells et al. [5454. Wells JA, Zipp JF, Schuette PT, McEleney J (1983) Musculoskeletal disorders among letter carriers: A comparison of weight carrying, walking and sedentary occupations. J Occup Med 25: 814-820.], examined the incidence of musculoskeletal injuries by letter carriers (load carrying & walking), meter readers (walking), and postal clerks (sedentary), they reported a direct relationship between musculoskeletal injuries and the more active occupations. The report also suggests a direct relationship between the intensity of occupational activity with the frequency of musculoskeletal injuries [5454. Wells JA, Zipp JF, Schuette PT, McEleney J (1983) Musculoskeletal disorders among letter carriers: A comparison of weight carrying, walking and sedentary occupations. J Occup Med 25: 814-820.]. Chaffin attributes the load-frequency association with the following: increased exposure to physical insult that may increase “wear and tear” on connective tissues; muscle fatigue; and uncoordinated movements [44. Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.].

In a study of airline transport workers by Undeutsch et al. [99. Undeutsch K, Gärtner KH, Luopajärvi T, Küpper R, Karvonen MJ, et al. (1982) Back complaints and findings in transport workers performing physically heavy work. Scand J Work Environ Health 8: 92-96.,1313. Undeutsch K (1984) The role of anthropometric measures on the musculoskeletal system of workers performing heavy physical work. Ann Physiol Anthropol 3: 211-216.], musculoskeletal injuries were related to the type of activity, the frequency of activity, and body weight. Back pain was prevalent in 66% of the workers, followed by knee complaints (41%). While all musculoskeletal complaints increased with age, knee complaints increased with the increase in body weight. In the study by Wells et al. [5454. Wells JA, Zipp JF, Schuette PT, McEleney J (1983) Musculoskeletal disorders among letter carriers: A comparison of weight carrying, walking and sedentary occupations. J Occup Med 25: 814-820.], letter-carriers experienced more shoulder problems when the letter carrying weight was increased. Wells et al. [5455. Svensson HO, Andersson GBJ (1989) The relationship of low-back pain, work history, work environment, and stress: A retrospective cross-sectional study of 38- to 64-year-old women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 14: 517-522.], also reported a similar rate of complaints in the lower extremities between letter-carriers and meter-readers. Luopajarvi et al. [5656. Luopajärvi T, Kuorinka I, Virolainen M, Holmberg M (1979) Prevalence of tenosynovitis and other injuries of the upper extremities in repetitive work. Scand J Work Environ Health 5 48-55.], compared the prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries of female assembly-line packers in a food packing plant to female shop assistants who had variable tasks. Shop assistants significantly had fewer musculoskeletal complaints than packers. In addition, packers significantly had more musculoskeletal injuries and experienced injuries more frequently than shop assistants. Most musculoskeletal injuries in the food packing project were variations of strains, sprains, and inflamed joints.

Discussion

Most of the reports described here as well as health care experts agree with the benefits of habitual physical activity on physical and psychological health. The funding and attention to the prevention and treatment of LBP with physical activity has been an understudied area compared to other health threats. In the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, the words “low back” or “low back pain” were found at two locations – multiple sclerosis and an adverse event [2323. (2009) Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. To the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Part A: executive summary. Nutr Rev 67: 114-120.]. The word “lumbar” was found four times, once for adolescent health.

The role of randomized clinical trials in the study of exercise for the treatment of low-back pain and injury is the standard by which other studies are compared [5757. Rimmer JH, Chen MD, McCubbin JA, Drum C, Peterson J (2010) Exercise intervention research on persons with disabilities: What we know and where we need to go. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89: 249–263.]. From studies that use research designs that were different from randomized clinical trials, much information can be learned and used as a framework that can be further studied by the randomized clinical trial. Challenges of the randomized clinical trial for exercise intervention with those with LBP may include sample size, selection criteria, and cost. Occupational and leisure-time LBP may contain subject characteristics that may be low-incident and difficult to recruit, or match with controls. The ethical issues with complete randomization also may be difficult to manage since the treatment for some subjects may be beneficial and the movement of subjects could include challenges for the institutional review board reviewing the study. Lastly, the costs associated with clinical trials that may include over-night accommodations or travel with the reimbursement of participants may be strenuous for the projects budgets.

The overlap of diagnoses and the separation of LBP between the type (occupational, leisure, accidental, etc.) and sub-type (acute or over-use) and location (thoracic, lumbar, sacral, etc.) further complicates the study of this disability with physical activity. Recruitment challenges, confidentiality of medical information used for harmonizing study groups, and intervention modalities are several factors that are influenced by consistent and homogeneous (disability type, gender, age, occupation, socioeconomic status, etc.) study groups.

The benefits reported by the reviewed therapeutic exercise studies were challenged by the research designs. The modest benefits by studies using aerobic exercise may have been resolved with improvements in the selection of participants and the design of exercise treatments. For the study by Chenoweth [2828. Chenoweth D (1983) Fitness program evaluation: Results with muscle. Occup Health Saf 52: 14-17, 40-42.], a selection bias was an important factor that could have affected results, where the only group of employees used was the (first) daytime shift, the selection of participant volunteers used for the treatment group included employees that responded to the recruitment notice, and the only randomized group were controls (from a computerized list of employees). Ages for the participants and controls also were not reported. No systematic determination of sufficient sample size was reported. Since the exercise intensity was not measured then the amount of activity may not have been of sufficient intensity to produce a larger training effect, which was documented in the modest benefits in the treatment group between the first week and the twelfth week while withholding results by the control group [2828. Chenoweth D (1983) Fitness program evaluation: Results with muscle. Occup Health Saf 52: 14-17, 40-42.]. Results from the Harkom study [2525. Harkcom TM, Lampman RM, Banwell BF, Castor CW (1985) Therapeutic value of graded aerobic exercise training in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 28: 32-39.] may have been more significant if a larger sample size was selected for each group which would have improved power. The participants were selected and did not include volunteer participants which infers a systematic selection process by the investigators. The determination of subjects for each treatment group was not randomized and the distribution of gender across the groups was not reported [2525. Harkcom TM, Lampman RM, Banwell BF, Castor CW (1985) Therapeutic value of graded aerobic exercise training in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 28: 32-39.]. An insufficient sample size for adequate power and significant differences between groups (such as gender) were complications also for the studies by Chan et al. [2929. Chan CW, Mok NW, Yeung EW (2011). Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition to Conventional Physiotherapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92: 1681-1685.], and Sculco et al. [3030. Sculco AD, Paup DC, Fernhall B, Sculco MJ (2001) Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J 1: 95-101. ]. Outcome variables were not measured at a sufficient duration (e.g., 12 weeks) where fitness changes may have been measureable in the Chan study.

Studies that used therapeutic muscular strength and endurance may have been improved with modifications to the outcome variables. The report by Hemborg et al. [3737. Hemborg B, Moritz U, Hamberg J, Löwing H, Akesson I (1983) Intraabdominal pressure and trunk muscle activity during lifting -- effect of abdominal muscle training in healthy subjects. Scand J Rehabil Med 15: 183-196.], contained results that implied the exercise programs designed to increase muscular strength of abdominal and back muscles of workers may not have directly affected the injury rate if the lifting loads did not change. Since the pre- and post-standardized testing protocol used the same weight for lifting, it was not determined if the training program affected lifting capacity of the subjects. The research by Chapman and Troup [3838. Chapman AE, Troup JDG (1969) The effect of increased maximal strength on the integrated electrical activity of lumbar erectores spinae. Electromyography 9: 263-280.] suggested the increased strength measured was attributed to gains in motor unit activity instead of hypertrophy of the muscle fibers. Nachemson [4040. Nachemson A, Lindh M (1969) Measurement of abdominal and back muscle strength with and without low back pain. Scand J Rehabil Med 1: 60-63.] showed that abdominal muscle strength may not be important for prevention of low back pain.

When different variations of exercise were the intervention (combinations of aerobic, muscle strengthening, and flexibility exercise), the potential changes varied depending on the intervention combinations. Cady et al. [4141. Cady LD, Bischoff DP, O'Connell ER, Thomas PC, Allan JH (1979) Strength and fitness and subsequent back injuries in firefighters. J Occup Med 21: 269-272.,4242. Cady LD Jr, Thomas PC, Karwasky RJ (1985) Program for increasing health and physical fitness of firefighters. J Occup Med 27: 110-114.] reported improvements in spine flexibility and concluded that the most fit employees experienced fewer injuries and incurred injuries which cost less to treat, however several changes may have affected the outcomes. First, the amount of flexibility, muscular strength, or physical work capacity was not stratified between the different categories of fitness. Second, the results were not adjusted for age, gender, body mass (height or weight), or man-hours of work (exposure). This lack of adjustment could suggest that the most fit could be lean, nonsmoking, healthy, young men who were at reduced risk of injury and the least fit included more obese, smoking, older men who had increased risk of an injury. No mention of difference between gender for fitness or low back injury incidence was made. In addition, the authors cited the least fit group of firefighters were older, therefore, the increased incidence of low back injuries in that group may not be due to fitness level but due to other factors such as age, longer smoking history, and longer man-hours of work (lifetime exposure). For the study by Kohles et al. [4343. Kohles S, Barnes D, Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG (1990) Improved physical performance outcomes after functional restoration treatment in patients with chronic low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15: 1321-1324. ], significant power may have been achieved if the terms for establishing an adequate sample size were included. A longer preprogram treatment period produced improved results with additional aerobic exercise and muscle strengthening but it remains uncertain if the activity, the educational component, or both, were responsible for the improved results; and, would a longer (optimal) preprogram treatment period achieve even better results should have been examined closer. Van der Velde and Mierau [4444. van der Velde G, Mierau D (2000) Effect of exercise on percentile rank aerobic capacity, pain, and self-rated disability in patients with chronic low-back pain: a retrospective chart review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81: 1457-1463.] could have included measures of physical activity more specific than the language offered in the patient’s medical chart. Though not pathological benefits, the study by Vad et al. [4545. Vad VB, Bhat AL, Tarabichi Y (2007) The role of the Back Rx exercise program in diskogenic low back pain: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88: 577-82.], reported indirect benefits that may provide sustained success of various forms of exercise as supplemental therapy and may be improved if the investigators instituted a narrow case definition of subject characteristics and coupled the activity with other successful therapies. As the affected vertebral disks ascend or descend the spine between participants, the moment arms of stress may vary from the additional load of trunk weight on the affected disk area. The narrowed definition of cases may help to reduce the scope from the varied moment arms of stress placed on the low back. By far the best organized and balanced study reviewed, the investigation by Oliver et al. [4646. Olivier N, Thevenon A, Berthoin S, Prieur F (2013) An Exercise Therapy Program Can Increase Oxygenation and Blood Volume of the Erector Spinae Muscle During Exercise in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94: 536-42.], provided informative results for the pathologies possible from various exercise. Their results suggest increased angiogenesis and muscle perfusion as a result of the treatment. Concomitant training effects may include reduced sympathetic stimulation and increased cardiac output. Other variables worth measurement for explaining the effects on participants would include oxygen consumption and blood lactate measurements. Hag berg [5858. Hagberg M (1984) Occupational musculoskeletal stress and disorders of the neck and shoulder: A review of possible pathophysiology. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 53: 269-278.] has reviewed the pathophysiology of an occupational musculoskeletal injury. In the musculature, changes include ruptured Z-discs, an outflow of metabolites from the muscle fibers, and edema which activates pain receptors. Ischemia also contributes to muscle pain, which contributes further to the accumulation of metabolic by-products, such as lactate. The production of lactate lowers the muscle pH and decreases the functional capacity of muscle enzymes, in addition to inhibiting the production of the muscle’s energy source, adenosine triphosphate (ATP). If work tasks are 10-20% of the maximal voluntary contraction and are performed too frequently, the result could produce enough ischemia to traumatize the muscle cells. This trauma could affect muscle cell morphology and energy metabolism. Hag berg suggested that proper strength training could avoid such changes.

The effects from occupational labor on metabolism and residual injuries were limited and not substantially productive for reducing further LBP. Previous research efforts have been unsuccessful in establishing a clear link between occupational physical activity and the occurrence of low back pain.

Study limitations

Probably the most significant limitation is the limited scope of a narrative review instead of the electronic literature search for a systematic review. A comprehensive approach to examining evidence-based published literature should contain elements of the following: specific literature search containing criteria defining the scope of the population (occupational or accidental LBP), subject headings of past and present exercise therapies (e.g., the rebirth of Pilates as a form of exercise therapy in the late 20th century) and therapeutic combinations (e.g., back schools), definitions of functional disabilities (pathologies involved, acute or chronic injury, extent of the disability, limitations of ambulation, etc.), specific characteristics of the research design (inclusion criteria, outcome measurement, interview type, single-subject versus group intervention, and criteria for exclusion), and cohort characteristics (age and gender specification, education, socioeconomic status, occupational class, ethnicity, religion (some limit the extent of therapeutic intervention), race, and marital status).

A recent clinical review of the state-of-the-science for LBP was published in the website Medscape [6060. Wheeler, A.H. (2013). Low back pain and sciatica. Chief editor: Berman, S.A.; Speciality Editor Board: Schneck, M.J., F. Talavera, & J.H. Halsey. ]. The review was authored by five clinical specialists and described the epidemiology, pathophysiology, therapeutic treatments and outcomes for low-back pain and sciatica. In addition to the recent reviews by others [5959. Minematsu, A. (2012). Epidemiology, Low Back Pain, Ali Asghar Norasteh (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-0599-2, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/35748. ], within the past 15-20 years the role of exercise in the treatment of LBP has not changed significantly, the effects of exercise therapy on LBP has not changed, and the incidence of LBP has remained relatively stable – LBP remains the most common cause of physical disability in Americans less than 45 years of age. Lumbar stabilization exercise was more therapeutic beneficial than lumbar strengthening exercise, and lumbar strengthening exercise may not have produced measureable benefits for LBP.

Future research

Since the level of a low back injury affects the trunk above the injury and the innervated segments below the injury, isolating the vertebrae that causes the LBP would be beneficial for subject selection for future research. Head and trunk movements are determined by the level where the injury or inflammation has occurred. The lower the damage on the spinal column the greater the flexion and weight of the moment arm that must be maintained by the injured back to maintain position of the upper trunk. The location of the injured vertebrae also determines the function of the lower trunk below the injury. If the injury location is different between study participants, then the ability for physical motion also will vary between participants. Future studies then should focus with selection of participants with the same location of back impairment.

The review by Granhed et al. [3939. Granhed H, Jonson R, Hansson T (1987) The loads on the lumbar spine during extreme weight lifting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 12: 146-149.], that discussed the effects of exercise to increase muscle strength and its effects on BMC presented evidence that has not been studied further. So far, no clinical or epidemiological investigation has been conducted to examine the relationship between bone mineral content and the increased frequency of musculoskeletal sprains of the back. Perhaps the addition of pathological evidence may help to establish proof of beneficial exercise, for example, angiogenesis and increased muscle perfusion documented by Oliver et al. [4646. Olivier N, Thevenon A, Berthoin S, Prieur F (2013) An Exercise Therapy Program Can Increase Oxygenation and Blood Volume of the Erector Spinae Muscle During Exercise in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94: 536-42.]. It would seem reasonable that a combination of measurements would be necessary to document the changes produced by a combination of exercise therapies.

Conclusions

Given the physical and financial burden to treat LBP, this issue remains a great public health importance. The risk factors for occupational LBP have been cumbersome to identify because the mechanisms of causation are not well-defined, the injury etiology may be puzzling, and the available research provide variable results. The indirect difficulties from occupational LBP (e.g., personal and familial financial burdens, psychological harm, social and legal problems, etc.) significantly influence LBP and disability. Inconsistent findings from research with therapeutic and occupational exercise (labor) provide confusing results for the high-risk elements [6060. Wheeler, A.H. (2013). Low back pain and sciatica. Chief editor: Berman, S.A.; Speciality Editor Board: Schneck, M.J., F. Talavera, & J.H. Halsey. ].

With the burden on society from LBP and the prevalence of the disorder among populations, research from physical activity on LBP has produced varied results without a specific type of exercise that results in resolved LBP better than most. Most agree that some activity is better than none, but no one activity is better than the rest when the multifactorial etiology remains inconsistent. Scientists have yet to discover a method of focusing on a specific pathology to a specific region of the spine that has been affected by the same muscles, tendons, bones, ligaments, and nerves and treat that pathology with a beneficial type of physical activity with consistent positive results.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of Point Park University, the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) or Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC)/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Mention of commercial products or trade names does not constitute endorsement by Point Park University, the NPPTL or CDC/NIOSH. The author does not have any financial interest in the present research.

- Karvonen MJ, Viitasalo JT, Komi PV, Nummi J, Järvinen T (1980) Back and leg complaints in relation to muscle strength in young men. Scand J Rehabil Med 12: 53-59.

- Kelsey JL (1982) Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Disorders. Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics. 3: New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sinkule EJ, Nelson RM, Nestor DE (1986) Musculoskeletal injuries in an aging workforce. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Engineering in Medicine and Biology. Baltimore, Maryland: Alliance for Engineering in Medicine and Biology, 364.

- Chaffin DB (1979) Manual materials handling: The cause of over-exertion injury and illness in industry. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 2: 31-66.

- Cunningham LS, Kelsey JL (1984) Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am J Public Health 74: 574-579.

- Kosiak M, Aurelius JR, Hartfiel WF (1968) The low back problem - An evaluation. Journal of Occupational Medicine 10: 588-593.

- Guthrie DI (1963) A new approach to handling in industry. A rational approach to the prevention of low-back pain. S Afr Med J 37: 651-655.

- Biering-Sorensen F (1984) Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine 9: 106-119.

- Undeutsch K, Gärtner KH, Luopajärvi T, Küpper R, Karvonen MJ, et al. (1982) Back complaints and findings in transport workers performing physically heavy work. Scand J Work Environ Health 8: 92-96.

- Nachemson A (1969) Physiotherapy for low back pain patients. A critical look. Scand J Rehabil Med 1: 85-90.

- Dehlin O, Berg S, Hedenrud B, Andersson G, Grimby G (1978) Muscle training, psychological perception of work and low-back symptoms in nursing aides: The effect of trunk and quadriceps muscle training on the psychological perception of work and on the subjective assessment of low-back insufficiency. A study in a geriatric hospital. Scand J Rehabil Med 10: 201-209.

- Andersson GBJ (1981) Epidemiologic aspects on low-back pain in industry. Spine 6: 53-60.

- Undeutsch K (1984) The role of anthropometric measures on the musculoskeletal system of workers performing heavy physical work. Ann Physiol Anthropol 3: 211-216.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2014) Physical Activity, Related Objectives (Adults). Department of Health and Human Services.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2014) Physical Activity, Related Objectives (Adolescents). Department of Health and Human Services.

- Pate RR, Blair SN (1983) Physical fitness programming for health promotion at the worksite. Prev Med 12: 632-643.

- Oja P, Teräslinna P, Partanen T, Kärävä R (1974) Feasibility of an 18 months physical training program for middle-aged men and its effect on physical fitness. Am J Public Health 64: 459 - 465.

- Jackson CP, Brown MD (1983) Is there a role for exercise in the treatment of patients with low back pain? Clin Orthop Relat Res 179: 39-45.

- Keyserling WM, Herrin GD, Chaffin DB (1980) Isometric strength testing as a means of controlling medical incidents on strenuous jobs. J Occup Med 22: 332-336.

- Buskirk ER (1985) Health maintenance and longevity: Exercise. In Handbook of the Biology of Aging, Second Edition. Edited by Caleb E. Finch and Edward L. Schneider. New York, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 894-931.

- Panush RS, Schmidt C, Caldwell JR, Edwards NL, Longley S, et al. (1986) Is running associated with degenerative joint disease? JAMA 255: 1152-1154.

- Rhodes EC, Dunwoody D (1980) Physiological and attitudinal changes in those involved in an employee fitness program. Can J Public Health. 71: 331-336.

- (2009) Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. To the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Part A: executive summary. Nutr Rev 67: 114-120.

- Tipton CM, Matthes RD, Maynard JA, Carey RA (1975) The influence of physical activity on ligaments and tendons. Med Sci Sports 7: 165-175.

- Harkcom TM, Lampman RM, Banwell BF, Castor CW (1985) Therapeutic value of graded aerobic exercise training in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 28: 32-39.

- Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC (1986) Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med 314: 605-613.

- Chapman EA, deVries HA, Swezey R (1972) Joint stiffness: Effects of exercise on young and old men. J Gerontol 27: 218-221.

- Chenoweth D (1983) Fitness program evaluation: Results with muscle. Occup Health Saf 52: 14-17, 40-42.

- Chan CW, Mok NW, Yeung EW (2011). Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition to Conventional Physiotherapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92: 1681-1685.

- Sculco AD, Paup DC, Fernhall B, Sculco MJ (2001) Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J 1: 95-101.

- Davis MF, Rosenberg K, Iverson DC, Vernon TM, Bauer J (1984) Worksite health promotion in Colorado. Public Health Rep 99: 538-543.

- Baun WB, Bernacki EJ, Tsai SP (1986) A preliminary investigation: Effect of a corporate fitness program on absenteeism and health care cost. J Occup Med 28: 18-22.

- Bowne DW, Russell ML, Morgan JL, Optenberg SA, Clarke AE (1984) Reduced disability and health care costs in an industrial fitness program. J Occup Med 26: 809-816.

- Gibbs JO, Mulvaney D, Henes C, Reed RW (1985) Work-site health promotion: Five-year trend in employee health care costs. J Occup Med 27: 826-830.

- Chen MS, Jones RM (1982) Establishing priorities in the wellness program. Occup Health Saf 51: 6-7, 36.

- Martin J (1978) Corporate health: A result of employee fitness. The Physician and Sportsmedicine; 6: 135-137.

- Hemborg B, Moritz U, Hamberg J, Löwing H, Akesson I (1983) Intraabdominal pressure and trunk muscle activity during lifting -- effect of abdominal muscle training in healthy subjects. Scand J Rehabil Med 15: 183-196.

- Chapman AE, Troup JDG (1969) The effect of increased maximal strength on the integrated electrical activity of lumbar erectores spinae. Electromyography 9: 263-280.

- Granhed H, Jonson R, Hansson T (1987) The loads on the lumbar spine during extreme weight lifting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 12: 146-149.

- Nachemson A, Lindh M (1969) Measurement of abdominal and back muscle strength with and without low back pain. Scand J Rehabil Med 1: 60-63.

- Cady LD, Bischoff DP, O'Connell ER, Thomas PC, Allan JH (1979) Strength and fitness and subsequent back injuries in firefighters. J Occup Med 21: 269-272.

- Cady LD Jr, Thomas PC, Karwasky RJ (1985) Program for increasing health and physical fitness of firefighters. J Occup Med 27: 110-114.

- Kohles S, Barnes D, Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG (1990) Improved physical performance outcomes after functional restoration treatment in patients with chronic low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15: 1321-1324.

- van der Velde G, Mierau D (2000) Effect of exercise on percentile rank aerobic capacity, pain, and self-rated disability in patients with chronic low-back pain: a retrospective chart review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81: 1457-1463.

- Vad VB, Bhat AL, Tarabichi Y (2007) The role of the Back Rx exercise program in diskogenic low back pain: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88: 577-82.

- Olivier N, Thevenon A, Berthoin S, Prieur F (2013) An Exercise Therapy Program Can Increase Oxygenation and Blood Volume of the Erector Spinae Muscle During Exercise in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94: 536-42.

- LaPorte RE, Montoye HJ, Caspersen CJ (1985) Assessment of physical activity in epidemiologic research: Problems and prospects. Public Health Rep 100: 131-146.

- Caspersen CJ, Christenson GM, Pollard RA (1986) Status of the 1990 physical fitness and exercise objectives -- evidence from NHIS 1985. Public Health Rep 101: 587-592.

- Rose CL, Cohen ML (1977) Relative importance of physical activity and longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 301: 671-702.

- LaRiviere, J.E. & E. Simonson (1965). The effect of age and occupation on speed of writing. Journal of Gerontology; 20: 415-416.

- Magora A, Taustein I (1969) An investigation of the problem of sick-leave in the patient suffering from low back pain. IMS Ind Med Surg 38: 398-408.

- Haddon, W. & S.P. Baker (1981). Injury control. In, Prevention and Community Medicine, Second Edition. Edited by Duncan W. Clark and Brian McMahon. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Co., 109-140.

- Andersson GBJ (1985) Permissible loads: Biomechanical considerations. Ergonomics 28: 323-326.

- Wells JA, Zipp JF, Schuette PT, McEleney J (1983) Musculoskeletal disorders among letter carriers: A comparison of weight carrying, walking and sedentary occupations. J Occup Med 25: 814-820.

- Svensson HO, Andersson GBJ (1989) The relationship of low-back pain, work history, work environment, and stress: A retrospective cross-sectional study of 38- to 64-year-old women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 14: 517-522.

- Luopajärvi T, Kuorinka I, Virolainen M, Holmberg M (1979) Prevalence of tenosynovitis and other injuries of the upper extremities in repetitive work. Scand J Work Environ Health 5 48-55.

- Rimmer JH, Chen MD, McCubbin JA, Drum C, Peterson J (2010) Exercise intervention research on persons with disabilities: What we know and where we need to go. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89: 249–263.

- Hagberg M (1984) Occupational musculoskeletal stress and disorders of the neck and shoulder: A review of possible pathophysiology. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 53: 269-278.

- Minematsu, A. (2012). Epidemiology, Low Back Pain, Ali Asghar Norasteh (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-0599-2, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/35748.

- Wheeler, A.H. (2013). Low back pain and sciatica. Chief editor: Berman, S.A.; Speciality Editor Board: Schneck, M.J., F. Talavera, & J.H. Halsey.

Table 1:

Summary of studies investigating the relationship between aerobic activities with LBP.

↑ aerobic capacity and muscular strength; ↓ joint pain

Controls: 46±11.5

12 months: No difference in pain or disability between groups.

Controls: 48.1±7.3

30 months: ↓pain Rx and physical therapy referrals; ↑ work status among exercisers